SILAS SKINNER'S OWYHEE TOLL ROAD

LONG BEFORE THE STATE HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT TOOK OVER THE RESPONSIBUTY FOR ROAD CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE. MOST IDAHO AND OREGON ROADS WERE NATURAL ROADS OR TOLL ROADS. NATURAL ROADS SUCH AS THE OREGON AND CALIFORNIA TRAILS REQUIRED LITTLE IMPROVEMENT OR MAINTENANCE. MANY MINING CAMPS, HOWEVER, INCLUDING FLORENCE, IDAHO CITY, ROCKY BAR, AND SILVER CITY, WERE INACCESSIBLE EXCEPT BY PACK TRAIN UNTIL TOLL ROADS WERE CONSTRUCTED. THIS STORY, WRITTEN BY STACY PETERSON IN THE SPRING 1966 ISSUE OF IDAHO YESTERDAYS, REFERENCE SERIES OF THE IDAHO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUMBER 427, DESCRIBES ONE OF THESE CENTURY- OLD TOLL ENTERPRISES, THE OLD SKINNER TOLL ROAD

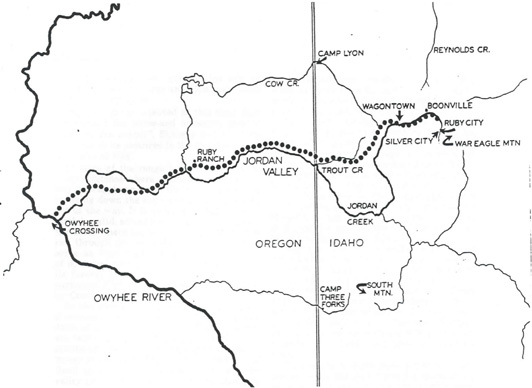

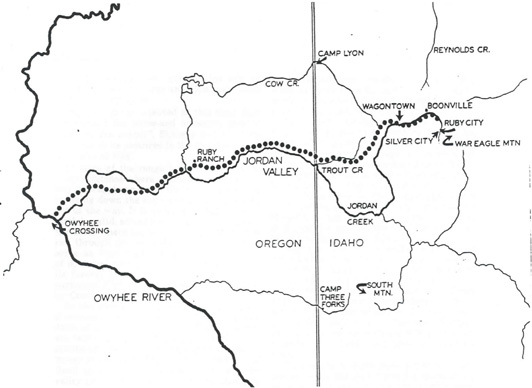

The Old Skinner Toll Road was one hundred years old on May 19, 1966. The approaching centennial has sparked a wave of renewed interest in this historic road, which in its heyday was one of the most important in the West. Extending from Silver City in the Owyhees down Jordan Creek seventy miles to its junction with the Owyhee River at Duncan's Ferry, it is rich with legend and history, and strewn with historic sites. It was conceived and built to provide the vital southwest outlet for the new and vastly rich mining district of the Owyhees ; and the saga of The Road is also the tale of its builder, Silas Skinner, from the Isle of Man. Gold was first discovered in the Owyhees in placer form, by a party of adventurers out from the crowded Boise Basin on a prospecting trip-or, some say, in search of the fabled lost Blue Bucket mine; twenty-nine men, with over sixty horses. They did not find the Blue Bucket, but they came on May 18, 1863, to a creek flowing out of the Owyhee Mountains on whose bars they found grains of the precious metal so numerous that they called the place Happy Camp,' and the creek for their leader, Michael Jordan, and soon that creek gave its name to a valley and a town. Eventually such names as War Eagle, Poorman, Golden Chariot, Ida Elmore, and many others came to be heard in mining talk world-wide. For the Twenty-nine had discovered a hoard which would attract investors from Europe', would help to pay for a war, and would enrich the nation for forty million dollars in fifty short years: The preliminary placer diggings soon gave way to the big business of hard- rock mining, and the rich lodes buried deep in the granite of War Eagle and Florida Mountains toppled world records: There was a great stir in Washington about a mint for Boise, to serve the whole Northwest mining area: But politics killed that dream, and Boise settled for "the handsomest assay office in the nation", while the mint went to San Francisco. So the fabulous harvest of the Basin and the Owyhee's had still to find its way on the backs of mules and horses picking their way among the lavas and over the deserts and streams to the headwaters of the Sacramento, or to Portland and the Ocean. The only certain outlet from the Owyhee mines at this time led northeast across the Snake and Boise Rivers to the Oregon Trail, there to join the pack-trains and freight wagons from Boise Basin. This involved first a fourteen-mile plunge down the northwest side of War Eagle Mountain, following the rocky bed of Reynolds Creek to the Snake River Valley, where a doughty pioneer named Carson had a ranch and corrals, and supplied meals and shelter to travelers. Ten miles farther on they crossed the Snake, by a man- powered ferry. Thirty miles of barren desert lay between them and the Boise River, and another primitive ferry, which served the city of Boise. Joining the packtrains and wagons from the Basin rnines, Owyhee packs followed either a northwest course to Umatilla and Portland, where they met the south-bound boat to San Francisco, or went south and east by the Oregon Trail to join the old immigrant route across northern Nevada and California, and finally south to the docks at Sacramento and by boat to San Francisco enroute to the Eastern seaboard or European ports. Both these routes were roundabout, slow and costly, and merchants, promoters, and the various governmental agencies had sought earnestly a more direct approach to the Owyhees. In fact, by the fall of 1863 several trails were in use, north from Sacramento and across the White Horse plains in southeast Oregon, as far as the Owyhee River. There they ended in confusion. The only crossing on the Owyhee was a ford and hand-operated ferry near the mouth of Jordan Creek far and wide this was known rather infamously as the Owyhee Crossing. Beyond it lay the meadows of Jordan Valley, boggy in Spring and Fall, impassable in Winter. Forty miles up Jordan Creek a daring soul named John Baxter had squatted on a ranch in a beautiful cove, and kept a sort of roadhouse and small general store. Beyond this the creekbed wound steeply upward twenty-two miles into the Owyhee". Here every pack, foot-passenger, and vehicle pioneered its own path. Nothing went beyond Baxter's in winter, but during several months in spring.

No one had yet invented the slip or the fresno, and Skinner and Company built their roads by hand. Though the press reported at this time that the demand for horse-and ox-teams greatly exceeded the supply, Skinner had his own oxen, which he pastured in the meadow along the right of way. In spite of the rough terrain, there were many stretches where construction consisted only in dragging a heavy timber along a slope, breaking down the sage, and rolling the lava out of the way. It is possible to follow these stretches still, across low-lying hills and grazing land, where parts of the Old Road now run through fenced fields and pastures, and serve as work-roads. At least fifteen miles of it, in and near the town of Jordan Valley, lie forever preserved beneath the blacktop surface of Highway 95, or the gravel of near by County and market roads. In two places Skinner and Company found it necessary to hew their road from the lava flank of a highland. Approaching its southern terminus at the Owyhee River, they encountered a lava hill which a modern earth mover would slash through; but here the Old Road comes down off a low divide into the valley of Jordan Creek and turns abruptly north, to stretch upward for an eighth of a mile on a ten per cent grade along the hill-side, then over the crest and down to Duncan's Ferry near the junction of the Creek and the Owyhee River. Here the road was cut from solid lava with pick and shovel, or sliced cleanly through a sandstone outcrop. Chunks of lava weighing a ton or more were blasted out and dragged aside by oxen to form a wall along the outer edge of the road, where they still lie. Again, near the opposite end of the Road, fifty miles to the east, climbing steeply toward Wagontown, the builders avoided a dangerous horseshoe gorge by turning off Jordan Creek to follow up its tributary, Trout Creek, and slashing along the flank of another lava barrier to top out on a stormy ridge. Six miles farther on, the Road dipped again to follow the Jordan up into the heart of the Owyhee camps. This Trout Creek grade is still passable most of the year for jeeps and trucks all the way to Silver City. Meantime two other problems demanded Silas Skinner's attention. First, his plan had expanded to include the northeast route from the Owyhees to Boise and the Basin. Of the already existing Reynolds Creek road, the first two miles, extending from Ruby City to Booneville, on Jordan Creek, was a free public road. The next fourteen miles, down Reynolds Creek, was a toll-road, franchised in 1864, and already in bad repair. To provide a dependable outlet for commerce, Silas Skinner formed a partnership with H. C. Laughlin, and bought this road. Having thus acquired another fourteen miles of difficult road to maintain, Skinner and Laughlin set about making their road usable. Precipitous and exposed on the cold northern slope of the mountain, carved from the rocky bed of Reynolds Creek, now on one side of the stream, now on the other, it was always hard to maintain, and always subject to complaint in the press. However, it was soon reopened, presumably under the Carson franchise, and a toll-collector put in charge. The first proved incapable, and according to the Avalanche Silas Skinner fired the wretch, and hired another, before leaving for Boise late in December on other business. He had as yet no franchise to operate any road or to collect tolls. Idaho had become a territory in March, 1863, following the discovery in 1860 of gold in the Clearwater area, and the capital was located in nearby Lewiston. The Boise Basin discovery of gold and silver, and the opening of the Owyhee lodes, attracted such an influx of population to the southern counties thut in 1864 the Second Session of the Territory, Legislature moved the capital to Boise. It was to the Third Session, sitting in the new capital, that Silas Skinner made application late in December of 1865 for franchises for his two toll-roads, both nearly completed, and ready for operation. Skinner stayed in the capital, watching the progress of his applications through the legislative mills, for the political attitude was not favorable to private roads. The long fight against private ownership and control of roads had already reached a considerable clamor, with Stephen Fenn of Nez Perce County its very vocal spearhead in the Legislature. However, on January 3, 1866, he received both franchises, duly approved by Governor Lyon.

Meanwhile his Reynolds Creek Road was closed for five days in direct violation of his parting orders. The Avalanche took explosive notice, but nevertheless declared Mr. Skinner is a man of high principles, who intends things to be done right, but he cannot be everywhere at once. These early franchises make interesting reading, and throw much light on the thinking of the times. They are wordy, detailed, full of after-the-fact requirements, and in some cases almost petulant. Silas Skinner must have had previous reliable sources of information, for, after all, the Road was near completion, and the Reynolds Creek road was in operation, and both met all specifications. The first franchise grants to Silas Skin- ner, H. C. Laughlin, their heirs, successors, and assigns, the exclusive right and privilege to establish and maintain a toll-road, beginning at Booneville and running along the route of the toll-road already owned by them, or within two hundred yards thereof, to the ranch on Reynolds Creek known as the Carson Ranch. The road shall be kept in as good repair as the season and snows permit, continues vaguely the franchise, and they shall build substantial bridges and culverts along said route, and when needed to grade such road, which shull be of sufficient width for wagons to pass. Skinner and Laughlin were required to post bond of $1000 with the County Auditor within sixty days, and to complete the roud within one year. The schedule of toll extended from five cents per head for sheep and swine to a three dollar toll for a four-horse team and one loaded wagon. The County Commissioner, might reduce the rates at any regular meeting. or purchase the road upon proper appraisal after five years. The term of the charter was fifteen years. The second franchise provided for the new and crucial outlet from the Owyhees southwest. It granted to Silas Skinner, Peter Donnelly and James Jordan the right to build and operate a toll.road commencing at Ruby City at the intersection of Main Street in Ruby City with the toll.road running to Booneville, and running from thence by the most practicable route down Jordan Creek to the boundary between the Territory of Idaho and the State of Oregon. The Organic Act of March 4, 1863, which established the Territory of Idaho, placed its western boundary on a meridian running through the mouth of the Owyhee. But since much of the area had never been surveyed, the Owyhee River was generally accepted as the boundarv. Thus Skinner's road was built to the Ferry, and some forty miles of it lay in Oregon. By this fortunate error the major purpose of the Road was served, and the traffic block in Jordan Vallev and at the Crossing was eliminated. The franchise stipulates that three fourths of that part of the road between Ruby City and Boonevil1e, the congested urban section, shall be made at least sixteen feet wide, and not more than fifty yards, in anyone place, shall be Jess than sixteen feet wide. Moreover, private roads for private use only may be built on the right-of way, between mines and mills, but may not interfere with Skinner and Company's road in such a way as to damage it, or prevent the collection of tolls. For this more extensive project, a bond of $2000 was required, and one year was allowed for its completion. Tolls were approximately twice those on the Reyn- olds Creek road. According to the press of the day, the booming commerce of the West was hanging on the progress of Silas Skinner's road. The long rivalry between the Columbia River and the Sacramento routes to Idaho had been gradually resolved in favor of the latter. More and more traffic was now going up the Sacramento to Chico and Red Bluff. and thence by a number of overland routes to Oregon, to converge at the Owyhee Crossing. Weekly, in 1866, the Avalanche reported increased travel, greater volumes of freight, more immigrants heading for the Owyhee and beyond to the Boise Basin. A typical report appeared on April 14. Three pack-trains numbering about seventy-five packs and loaded with staples arrived in Jordan Valley April first, and in Ruby City last week. One week, to cover twenty- two miles! On April 21 the Sacramento Union was quoted to the effect that: A train of wagons built in Sacramento to carry 4500 to 6000 pounds each, and drawn by four animals, will leave for Idaho; expect to reach destination ahead of all competition. One hundred horses, eight mules, eight yoke of cattle, twenty-five wagons and thirty men. The enthusiastic editor exclaimed that all this only illustrates what can and will be done when Skinner's road is finished; all kinds of travel can come into the heart of the Owyhee mines the year round from Nevada and California. Two weeks more, at the furthest. But Skinner and Company were not ready; they issued an immediute correction. "Silas Skinner says," announced in the Avalanche on April 28, "the road from Baxter's Ranch up Jordan to this place will be passable for loaded wagons on and after the lOth of May, The grade is light all the way, and only twenty miles to the Valley." Finally, on May 19, the long-awaited announcement appeared : (The Ruby City and Jordon Valley toll-road is now in good order for teams, empty or loaded. By this road it is just twenty miles to Baxter's Ranch, and the only direct or even passable one to the valley and the Owyhee crossing on the Nevada and California roads. It is built on the north side of the creek, thus giving it the full benefit of the sun to keep it dry. Mr. Skinner informs us that the Company will keep it in good traveling order the entire year.)

Meanwhile Skinner and Laughlin had brought the Reynolds Creek road up to specifications. They established a toll-station just below Ruby City, to command both roads, and controlled all traffic through the Owyhees. Silas Skinner and his partners were actively in business. The Central Pacific Railroad was building eastward toward its junction with the Union Pacific, and trains were daily met by stage-coaches and freighters "at the end of the rails, wherever thut might be." Captain Mullan was making a second gallant try for control of the stage business in the area, supported by a mail-contract held by his brother-in-law, and outfitted with a fine new line of coaches and horses from the East.& Hill Beachey had just bought what was called the Railroad Stage Line. The California Steam Navigation Company and the Central Pacific combined to subsidize the Idaho trade by hauling goods free from Sacramento to Chico, cutting rates to Silver City to an unheard-of ten cents per pound and the citizens of Sacramento were raising a bonus fund of $5000 for the first freight-train to carry one hundred tons of merchandise to the Owyhee mines by way of Truckee. It was a triumph for Skinner and Company, too, that even before the opening of the Road the Teamsters Association of San Francsico advertised special rates in favor of goods shipped to the Owyhees by way of Susanville and the Skinner Toll-Road.

Skinner's dream was now realized, as traffic of all kinds flowed freely from the Pacific to the Owyhees, over the Reynolds Creek road to the Snake, and beyond to Boise Basin and points east, north, and south,-even as an early advertiser had boasted, "to all parts of the world !". There was much complaint in the press and in legislative halls about the lax upkeep of toll-roads. Early accounts tell of stage- passengers lifting coaches across swollen streams, while trudging alongside through the mire. "But every gate was closed," concludes one such story, bitterly, "and the toll- keeper taking tolls as usual." David Shirk writes, however, that on the Skinner Road "It was customary, as well as an established rule, for one of the partners to go over the road once each week, looking after repairs and exercising a general supervision over the road." In winter a man and team went ahead of the stage each day, to make sure the Road was open. The personnel of the Company changed from time to time, but the name of Silas Skinner remained; the Road was known through-out the West as the Skinner Toll-Road.

In 1867, Silas Skinner left the Road and the toll-station in his partners' care and took ship from San Francisco for the Isle of Man, for a visit with family and friends, whom he had not seen for five busy years. He returned again in 1870, and there in the Parish of Andreas, in the Isle of Man, he and Ann Callow were married in Kirk Andreas, where for centuries Skinners and Callows had been christened, married, and buried. They returned to Ruby City briefly, but soon moved to the upper Jordan Valley, where they built their home beside a peren- nial spring at the side of the Road, near Trout Creek bridge, where the Road turns off to climb the Trout Creek grade. The home was also a popular overnight station on the Road before the climb up the mountain to Ruby City. The house is gone now, but the spring bubbles among: the willows, and the Road still winds along, preserved beneath the gravel of the County road.

While the mines prospered as never before, settlers flocked to the Valley. By 1869, a correspondent listed eleven fine ranches on Jordan Creek and its tributaries. Bands of sheep were not uncommon on the Road, and in 1869 Con Shea and his partners brought a herd of longhorn cattle from Texas, to revolutionize the industry of two states. School was held in an upper room of the State-Line House, until a schoolhouse was built nearby. Everyone prospered. Hay sold for $100 per ton. The prophsey made by a traveling reporter in 1869 came true: "Jordan Valley excites the admiration of all travellers . . . In a few years it will be a paradise." When in 1875 the sudden Bank Panic in San Francisco closed most of the mines, and the boom faded, it was replaced by the stable economy of the ranches and the herds, and prosperity continued unabated in the Valley. But here as elsewhere in the west, peace and prosperity faced constantly the twin dan- gers of Indian raids and highway robbery. Fort Boise had been established as a United States Army post in 1863, but pleas for government protection were largely ignored during the war years". Finally, in September, 1865, four permanent military posts were built along the Sacramento-Owyhee route. These ranged from Smoke Creek in California, Pueblo and Camp C. F. Smith in the Whitehorse country of southeast Oregon, to Camp Lyon, on Cow Creek. to guard Jordan Valley and the Skinner Road. The entire road is now protected by troops from permanent military posts, declared the Avalanche. Eight or ten men are on duty at each [stage] station. Camp Lyon was beautifully located, and just where it was needed. Actually, Camp Lyon boasted three Companies, with two lieutenants and one sergeant, but the protection was far from adequate. Soldiers were war-weary, and entirely ignorant, if not fearful, of Indian fighting. Women and children still huddled in fortified dwellings during Indian raids, while their men fought off the enemy. Soldiers seldom leave their quarters, said one caustic comment, "and while they sleep the Indians steal their blankets. . . " That was generally the result, when there were no citizens with them, comments Shirk. Sent out under command of a sergeant, they accomplished little.

Thus was ushered in the savage uprising of 1868, which raged up and down the Road, and the Valley, until General Crook, of the United States Cavalry, defeated the Indians and brought an uneasy peace which lasted ten years. In 1878 occurred a much greater uprising, involving many of the Northwest tribes which ended only with the dispersal of the remnants of the tribes to Reservations. Principal patrons of the Skinner Toll-Road during these turbulent years were the freighters and the stagecoaches. Freighters travelletl for protection in companies of ten or more, each team consisting of four to ten span of horses, mules, or oxen, and hauling at least two wagons loaded to capacity. From Sacramento to Ruby City, the trip took twenty-five days at best, driving ten to fifteen miles per day. Oxen were scarce and expensive, but were preferred to horses and mules for their great strength, their placid natures, and easy maintenance. Moreover, they lived well off the country. An ox-team might with care be driven two thousand miles in a season, and come through fat on forage alone. Especially susceptible to attack from both Indians and outlaws, the lumbering freight trains, loaded with provisions, had little choice but to camp in circles about their fires, post guards, and shoot first. There seems to have been little dependence on the protection of the military. One big outfit acdvertised in advance. We ask no escort from the government, but expect to protect ourselves from Indians and all other adversaries by ourown vigilance and energy. Pack-trains, usually laden with treasure from the mines, seem to have suffered little. The tribes had little use for gold and silver, and "the knights of the road would much rather face the United States Army than a train of hard-bitten muleskinners." As for the stages, one movie-type story illustrates their special vulnerability to outlawry. A company of fifteen persons conspired to rob all the stages plying between Elko and Pine, on the same day (in August, 1869) . Seven of the group were captured when one, perhaps a Wells-Fargo detective in disguise, confessed and named the others. All were found to have been station-keepers for the Stage Company, or ranchers who hud settled along the roads between the railroad and the mines in order to carry on the road-agent business unsuspected. Wells-Fargo guards often proved more effective than the troops; but the main reliance of the stager lay in a good road, a fast team, and straight shooting. Captain Mullan's fine new line made its first trip from Chico to Ruby City by way of the Skinner Toll-Road in July of 1866, in the record time of three days and five hours, bringing papers and mail which previously took 18 to 50 days. Coaches will leave every other day, continued the press notice, connecting with HiIl Beachey's line at Boise City. Fare, $60. The coaches are excellent, and time not exceeding three days. But careful searching of old files indicates thut this was the only trip ever made by the dashing Captain. In 1868, HiIl Beachey, a veteran of staging, owner of the Mullan Stage-Line, secured both the coveted mail and express contracts, and made a dependable service of staging to and through the Owyhee.

Stations on the Skinner Toll-Road, as elsewhere, were located ten or fifteen miles apart, a good day's travel for a fast team. Many were crude one-room shelters, while others resembled fortresses set in expanses of ranchland. All provided sheds and corrals for stock, access to water, and camping facilities for travellers. Frequently, staple provisions were for sale, and at least one station-master kept a well-concealed barrel of whiskey which he would uncover for a price. Provender was available for stage stock only, and in the early years forty percent of a freighter's load was stock-feed. Later, Jordan VaIley ranches supplied all the hay the travelling public required. Two historic Stations on the Road still exist. One, the Ruby Ranch, had been located in 1863 by Dr. E. W. Innskip and his partner Osgood, as a likely spot for a wayside hostelry. One of the most important stations on the Road, it was independently operated through fifty years by a succession of owners. Later occupied as a ranch-house, it is now rapidly falling into decay, though across the Road stands a well-preserved wooden barn built a century ago and still in use. A typical "fortified dwelling", built of lava blocks, with port-holes in every wall, the Ruby Ranch often served as a refuge during Indian raids. (It boasted separate parlors for ladies and for gentlemen), the latter equipped with the only bar on the Road, - a simple cupboard, till recently still to be seen in the crumbling ruin. Great fire- places heated the rooms, and the weary traveler was provided rest and food while the teams were changed. Sheep Ranch is the other site; circled by tall poplar trees, this handsome landmark, the picture of hospitality, still stands, twelve miles down the Jordan from the Ruby Ranch. It is owned by the Eiguren family, .and was recently occupied by them. Its rock walls are twenty inches thick, with numerous portholes and great stone chimneys. It was the only Home Station, or overnight stop between Silver City and Fort McDermitt. Meals were served, staple groceries and tobacco were for sale, and on the first floor were three tiny sleeping rooms for ladies. Upstairs, reached only by an out-side stairway, were quarters for men. Wells- Fargo maintained an office at the Sheep Ranch, and here was located the only telegraph station in Jordan Valley. This building is worthy of preservation as a museum of a century of history along the Road.

Even during the hey-day of the Road and of mining in the Owyhees, Silas Skinner seems to have foreseen the end of both. He began early to diversify his interests by investing in mines and ranchland. Later he brought from Kentucky the foundation of a herd of fine horses which he bred for, the carriage trade and the race courses of California. He also contracted annually with the city of San Francisco for one-hundred-fifty draft horses for use on the streets. William Skinner, in a series of interviews which appeared in the Argus-Inquirer of Ontario, Oregion, in 1951, provides data on the latter years of the Road. After 1873, he says, the Road was managed by E. H. Clinton, who had bought the interest of the Jordan brothers, Michael and James. Silas Skinner disposed first of the Reynolds Creek Road, retaining the station at Trout Creek and the section of the Road extending from Jordan Creek to Silver City. By 1878 Owyhee County had purchased all that part of the Road which lay in Idaho, from the State Line in Jordan Valley, through the Owyhees, and out to Carson's station "in the desert". In October, 1878 Captain Bachellor bought the Trout Creek Station, and the Skinners moved to a new ranch home further down the Valley.

As time passed, Silas Skinner became concerned about the education of his children, and established a new home in Napa Valley, in California. He moved his horse-breeding enterprises there, leaving William, a boy of fifteen years, to manage the Jordan Valley ranch. When Silas Skinner died in 1886, the family disposed of the California interests and returned to Jordan Valley, where the Skinners have been through the century an active force in the growth of the community which the first Silas Skinner opened to the world. With the growth of new towns in the lower Boise Valley, a more direct contact with the Coast was needed. Several routes were opened from Snake River through the hills, by- passing the dying mining towns, and joining the Old Skinner Road in the town of Jordan Valley. Finally, in 1944, the present Highway 95 was completed with Federal aid, and became a part of the national defense system. It follows from the town of Jordan Valley west on a section of the Old Toll Road. Silver City is now a well-known ghost town, included on the itineraries of many tourists, some of whom have been known to by-pass it when they find they cannot reach it by the Old Skinner Toll-Road. There is much of color and historic as well as human interest to be found along the Road, and it is to be hoped that before time obliterates its appeal, interested Idahoans and Oregonians will see that this is preserved for the enjoyment and enlightenment of future generations of Americans.